This article examines the history of signatures, their psychological meaning and how graphology can help in the forensic examination of signatures. (Graphology describes the personality of an author, while forensic handwriting suggests who is the author.)

History of Signatures

Handwritten signatures are marks that show approval, obligation and identity and are sometimes accompanied by a ceremony to demonstrate personal involvement. They have, however, been accepted only relatively recently in Britain as a way of authenticating documents.

Key Dates

- The oldest signature to be discovered was on a tablet recording measures of barley and was written by an 'accountant' called Kushim in Sumer (part of ancient Mesopotamia) in 3,400 BC.

- Compiled in Galilee in the fourth century BC, the Talmud, the book of Jewish law, required all marriage contracts to be signed.

- During the long reign of Valentinian III (425-455 AD) Romans cast aside complex signets and replaced them with signatures and sentences about themselves at the bottom of documents.

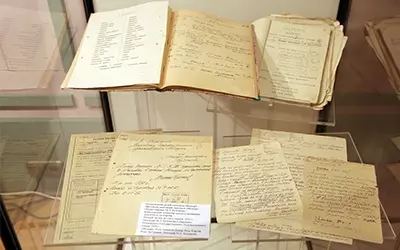

- With the increasing use of signatures, the Justinian Code (539 AD) outlined the duties of 'comparatores', who were experts at comparing handwriting and assessing forgeries.

- The sign of the cross: in 410 AD when the Romans left Britain there was a collapse in Christianity and literacy. At the end of the sixth century Pope Gregory the Great sent missionaries to England to fight paganism. Subsequently in the ninth century Irish monks copied manuscripts for distribution and to confirm they had done their best, a cross, symbolising the Christian oath of truthfulness, was placed at the end of the manuscripts. This mark continues today to be used by those unable to sign their own name.

Why were signatures slow to be accepted in Britain?

The reason for their slow acceptance was because of the wide use of seals and the oral tradition.

The use of seals dates back to a time earlier than the first signatures. During the period 8,000 to 7,500 BC, Sumerian farmers began to keep records of the goods they owned and small clay tokens with markings were formed as cones, spheres, disks, cylinders, etc with each shape standing for a particular commodity and different sizes denoting quantity. As storage was often in shared facilities, the tokens were kept in a round clay envelope and a seal impressed into the opening before the clay ball set hard. If a reckoning was required, as to who owned what, the clay ball would be broken open. This system of tokens lasted for four thousand years.

In Roman Britain, seal impressions on bitumen were used for military units, urban authorities and private individuals.

From the sixth century papal documents, to denote their authenticity, were 'signed' by attaching the papal seal to a document with a cord.

After the Romans left Britain, the earliest English documents known to be authenticated by seals, based on the design of the papal documents (bulls), were the writs of King Edward the Confessor (1042-1066).

The most famous seal was that of King John which was used to 'sign' the Magna Carta in 1215.

During the medieval period a person could ask the local bishop to borrow his seal and have his name noted, but by 1300 AD the use of seals had grown to such an extent that a personal seal was owned by a majority of people. The Statute of Exeter (1285) even required bondsmen to have seals to authenticate their written evidence and in 1413 the forging of seals was declared a felony.

It was some time before a signature or sign manual was accepted by itself as a lawful symbol of authentication on a document. Signatures and seals were used in parallel, as illustrated by the death warrant for Charles I (1649), where both the signatures and seals of the 59 commissioners were placed on the document (see below):

During the late 17th and 18th century with the rise of the middle classes (who practised penmanship for commercial activity) the trappings of martial glory and aristocratic lineage shown in seals became less relevant. Common seals tended to look the same, so seals did not distinguish a man. On the other hand, as stated by Geoffrey Gilbert in 'The Law of Evidence' (1726), the differences between men's handwriting could serve to identify them.

Socrates (470-399 BC) maintained that writing weakens the memory and that you can interrogate a speaker but text is mute. The strength of this oral tradition was maintained in Britain up to the 1300s. The word 'record' meant to bear oral witness and speaking to witnesses was considered more authoritative than writing.

People found it difficult to transfer their faith in living witnesses to passive documents, as handwriting implied mistrust. It was considered that an honest person held to his word, so there was no need for written proof. This attitude was illustrated by Henry I (1100-1135) when he argued with Archbishop Anselm about the authority of a papal bull. He wanted to speak directly to the pope's bishops. He said the papal document was merely " the skins of wethers (goats) blackened with ink and weighted with a little lump of lead".

Although the priority of written documents over personal testimony started to be accepted in the thirteenth century, up to the middle of the 17th century the importance of seeing and hearing was maintained with the tradition of Livery of Seisin (delivery of possession) for property transfer. At this ceremony, a formal set of words was pronounced and there was a transfer of a symbolic object, such as a piece of turf or a twig. Livery of Seisin survived for a long time, illustrating the general suspicion of writing, and remained legal in Britain until 1925.

Why did the use of signatures increase?

The reason was a combination of the increasing importance of names, increasing literacy and Acts of Parliament.

Importance of Names

Up to the 12th century, surnames were only used for the elite and clergy. At that time 40 percent of the poor were named John, Thomas or William. With the increase in government bureaucracy, the increase in monetary transactions, the increase in travel (when more people met with strangers) surnames were needed to distinguish people with similar Christian names.

Surnames are part of the modern world because they allow the state to pin down its subjects. But before 1350 most second names were nicknames and were selected by making reference to a person's occupation (e.g. Smith, Taylor, Fletcher, Cooper), where they lived (e.g. Wood, Marsh), their personal characteristics (e.g. Strong, Small); or they could be the result of a person taking their father's name, e.g. Johnson, for son of John and Macdonald for son of Donald.

Increase in literacy

Although there is a debate among historians as to what exactly literacy means (it appears the skill of reading was far more important than writing) the estimates below show a steady increase in literacy over time:

| Year | Men | Women |

|---|---|---|

| 1500 | 10% | 1% |

| 1715 | 45% | 25% |

| 1841 | 65% | 50% |

Before there was much literacy in terms of writing, little value was placed on handwritten signatures. But in1836, with the increase in handwriting literacy, the principle that a person could be identified by their hand writing was established in English Law with the case of Doe v Suckamore.

Impact of Law

Legal statutes had an impact on signing because of the emphasis placed on the recording of names.

- In 1597 The Clerical Ceremonies Act, organised by Thomas Cromwell, required names to be recorded in registers of baptisms, weddings and funerals, officiated by the clergy.

- In 1606, a year after the Gunpowder Plot, the Oath of Allegiance required all Roman Catholics to sign allegiance to James I.

- In 1643 the Solemn League and Covenant required all males over 16 to sign the covenant in front of witnesses. Parliamentary forces needed assistance from Scotland against Charles I and the Scots would only agree if members of the churches of England and Ireland agreed, by signing the covenant, to work for religious union under the Scottish Presbyterian system. (The covenant was repealed by Charles II with the Sedition Act of 1661.)

- In 1677 The Statute of Frauds stated all conveyancing of land had to be signed, certain contracts were unenforceable unless signed and sales of goods over £10 had to have a signed receipt.

- In 1753 the Marriage Act required the name of the bride and groom to be signed in the register and by then 60% of men and 40% of women were able to do so.

- In 1837 The Wills Act stated that wills were only valid when signed in front of witnesses.

What is acceptable as a signature?

The broad definition of a signature was outlined in 1874 with the case of R. v Kent Justices. The court decided: " A signature is the writing, or otherwise affixing [of] a person's name or a mark representing his name by himself or by his authority... with the intention of authenticating a document as being that of, or binding on, the person whose name or mark is so written or affixed".

In English common law your own name does not belong to you. What you own is your mark, a graphic device which may or may not be your name. The mark represents the will and intent of a person, aims to prevent that person repudiating a previous position and bolsters a document by disallowing anything under the signature or mark.

From the 19th Century a range of marks have been accepted as signatures, with the emphasis always on intent and the avoidance of fraud, for example:

- Initials on their own.

- A surname on its own

- A signature engraved on a stamp and applied by a third party in the presence of the person concerned.

- A mark that does not include any part of the name.

- Part of a name (a woman's signature was accepted even though she fainted before completing it)

- An assumed name which is not the person's real name but is intended to represent that real name. (The insistence that a person has a fixed standard name has little basis in common law.)

- The words: 'Your loving mother' accompanied with the name on the document.

- A guided signature when the top of the pen is guided by another person to form the name.

- Blood splotches, accepted in some states in the USA.

Present Situations

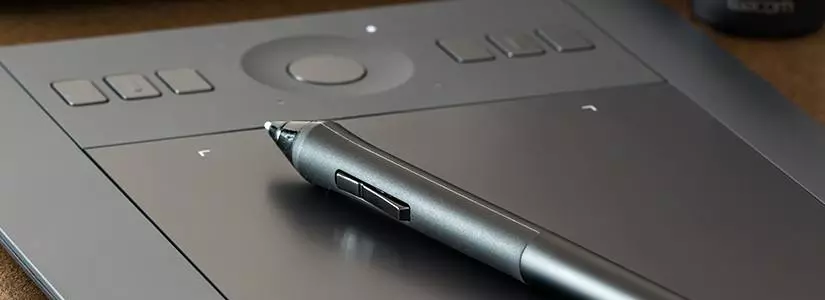

The modern world requires speed and convenience and electronic signatures are becoming more widely spread. Electronic signing can be with a digital signature or by digitising a standard signature.

Digital signatures: A digital key is affixed to an electronic document. The 'signer' puts in a password and a 'private key' generates a long string of numbers that represent the digital signature. The recipient of the document runs a software program using a 'public key' to authenticate that the document was in fact signed by the owner of the private key.

Digitised signatures: A person writes their signature a number of times with a stylus on an electronic pad or equivalent. The system records the timing of every stroke, the exact sequence and location of strokes, the pen acceleration and deceleration, along with pen pressure. Once the initial signature is captured, the system tracks its variations over time, updating the signature profile every time the user signs. This means a digitised signature can be verified anywhere in the world. Even if a forger obtains an authentic signature, it would be impossible for that forger to duplicate the range of biometric measurements on the system.

Law Commission: Although contracts of guarantee (surety for another's debts), patent applications, wills and land transfers still need signatures attached to documents, the Law Commission, after 20 months of investigation concluded in September 2019, that electronic signatures were a legally viable alternative on deeds ranging from trust documents to powers of attorney, commercial deals and personal financial transactions. But the commission warned that an electronic signature is not always acceptable. It said: 'not all stakeholders are convinced that an electronic signature fulfils the statutory requirement for a signature and this doubt can slow down transactions and lead to disputes'. Furthermore, it stated that some electronic signatures could be open to fraud.

Concerns

Compared with pen on paper, some people have concerns about digital signatures which are just a string of numbers:

- Authenticity: passwords can be stolen.

- Non-repudiation: how can the 'originator' of the electronic signature be prevented from refusing to take responsibility for their electronic signature? A digital signature connects to a device and does not identify an individual. For example, there was the case of Dr Susan Silver who sued her laboratory for adding her electronic signature to a report without her consent.

- Confidentiality: how is it possible to prevent someone breaking into a digital signature? In the USA the National Security Agency has said that it is building a computer that can crack most types of encryption. Hackers are continuously increasing their skills.

- Future examination: will people in the future know how an electronic signature was applied, especially after the IT people concerned have retired? At one trial the I.T. witness was not considered credible because he could not explain how an electronic signature had been attached to a document. As a result American Express lost the case.

- Global acceptance of one system? It is not efficient for a business to use multiple methods of signing. An American hedge fund sued the French bank BNP Paribas, alleging that it botched a £531 million Islamic bond backed by a Gulf tycoon. The complaint was that the French bank failed to make sure the signature on the note was a wet-ink original, a requirement in Saudi Arabian law.

Handwritten signatures are likely to remain in use

There are many methods of defining identity such as PIN numbers, fingerprints, facial recognition, iris checks, voice recognition, DNA, heart beats and behavioural biometrics (typing style). Not only do some of these approaches have problems but signatures are more than identity. A signer shows that they identify with a particular document and that they are bound by the contents.

Humanity has the capacity to add innovations without losing old habits. Writing one's signature is an old habit, practised from the moment a person starts to write. Handwritten signatures, on paper or digitised, are, therefore, likely to exist in the future.

Graphological Meaning of Signatures

Ideally signatures should be analysed in conjunction with the ordinary cursive script of the author. The reason is that there can be differences in style between the signature, which is the public image, and the cursive text, which gives indications of the inner personality.

In other words, a signature may attempt to show an extravert character, while the cursive writing itself may show a more introverted and quieter personality. By emphasising a signature, a person may over-compensate for feelings of a lack of self esteem.

Signatures are usually developed early in life and signatures, once settled, do not always change along with the increasing graphic maturity of the writer, thus signatures can retain infantile feelings and show signs of a freedom not necessarily seen in the cursive writing of the mature adult. But with the increased use of typing on computers, etc. it is often only a signature that can be examined.

The above caveats need to be taken into account when assessing a signature on its own because, without sight of the cursive writing, a distorted picture could be developed. Nevertheless, although there are problems examining signatures on their own, they are not meaningless; personality characteristics can be discovered.

The complete range of graphological checks need to be made before drawing a conclusion about the personality, but below are some of the questions that need to be answered.

What is the main symbol present in the signature?

Circles

Those with circles tend to be people who seek approval and are loving, although they can be manipulative. They like comfort and time for their friends, but dislike being alone or having to make quick decisions.

Squares

These people tend to be logical and practical and not idealistic. They like procedures and details and do not always like delegating.

Triangles

These people are decisive and ambitious but also destructive and self-centred. They like awards and the 'top floor' and do not like wishy/washy people.

Thready

These people are creative and intuitive but tend to reject routine. They like freedom and thinking on their feet but do not like being organised by others.

The Relationship Between...

The Names

The relationship between names gives an indication of the person's reaction to family ties. The given name, the first name, is the intimate part of the ego, representing the person's private life, while the surname represents the social ego, the acceptance of the adult role. When all names are balanced they reflect a harmonious relationship between the private and social roles.

Overemphasis of the first name, possibly through greater legibility or size, can show a direct, friendly and approachable person or somebody with a strong need to attract attention. On the other hand, overemphasis on the family name may indicate family pride, feelings of prestige or a preoccupation with status but can also mean a person who is reserved on first contact. The spacing between names can indicate, if they are very far apart, a possibly unhappy childhood. With women a considerable distance between the given first name and the married name could mean problems in the marriage.

The Zones

Large upper zone

A symbol of mental force, this shows a person who needs to impress (and it could also mean a tendency to be overbearing). It is an exaggeration, so is a sign of a lack of inner assurance.

Dominant middle zone

This shows the importance of social activity. With narrow letters, as seen in the example, it means 'externals' are what matter.

Large lower zone

The lower zone expresses impulses and unconscious drives. In this example, there is displaced pressure in the lower zone, i.e. the pressure is on the up stroke rather than the down stroke, a sign this person has a strong need to attain.

How legible is the signature?

Legible signatures show a person who wants clear communication with others, who has a consideration for others, is punctual and orderly with a good capacity for purposeful work. An illegible signature may be a sign of self-protectiveness, mistrust, or someone who does not want to be recognised. (Note: however that some signatures disintegrate because the person has to sign many signatures every day.)

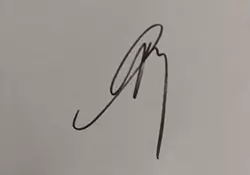

If the signature is completely illegible it may be a sign of deceit or somebody who does not wish to be tied down. Pictured right is the signature of the man who ran the largest criminal $65 billion Ponzi scheme in American history.

What is happening...

With the base line (the imaginary line under the signature)?

- When the signature is level it means the person has a consistent feeling about themselves - they are assured in their private as well as their public life.

- When the signature falls it is a sign the person may be discouraged or have difficulty working under pressure.

- When the signature rises it means the person is optimistic, has ambition and is a person who focuses on the constructive things they want to accomplish.

At the end of the signature?

The start of a signature is written more consciously than the end of a signature, so it is useful to check the final movements, which are made more unconsciously, for example:

- The final stroke completely encircles the signature. This is a symbol of anxiety; here is a person who craves re-assurance.

- The signature is underlined. This is the sign of a self reliant person.

- The signature is crossed through; here is a person who may be disappointed with their achievements.

- The final stroke is very heavy and may be pulled down below the base line. Here is somebody who insists on the last word in a conversation.

- The signature is followed by a full stop. This is a sign of cutting off, a safe guarding gesture.

- The end of the final letter is lifted well into the upper zone (for example the ending of 'n'): this means an excessive need for attention.

Forensic Examination

Forensic handwriting examiners compare questioned signatures with known/authentic signatures on the basis of: movement (speed, rhythm, pressure patterns, line quality, skill level); spacing (size, proportions, alignment) and form (starting/ending strokes, forms of connection, forms of construction).

Samples are considered to be written by the same author if there are significant similarities without any significant differences. Handwriting is considered to be simulated or copied if significant differences with the known writing cannot be explained. (Significant movements are those made unconsciously, with difficulty or are inconspicuous.) If a known and questioned signature are identical then tracing or computer transfer are likely to have taken place, because no two signatures are ever identical.

Materials involved in document examination are, for example, paper and ink. Examiners check these materials for alterations, erasures, impressions, indentations, cuts, perforations and readability (when charred or soaked). Such materials are relatively stable over time. But this is not the case with signatures. Signatures vary as they are produced under different circumstances, e.g. different writing surfaces, varying space available, different pens used, varying health of the writer, different occasions - formal versus private.

Document examiners use an understanding of physics and biology for their work but for the handwriting element of document examination there is no exact science upon which to draw. This is a problem for document examiners who have had to cope with the famous 'Daubert' cases in the USA. One of the judges, Lawrence McKenna, for example, ruled in April 1995 that forensic document examiners were not scientists, but were more in the nature of skilled craftsmen.

Because of this attitude from some courts, forensic handwriting examiners make no mention of any graphological/personality aspects - as discussed in the previous section. The reason is that graphologists share similar problems with forensic handwriting examiners in that their activity is not recognised as a science (as tested by the scientific method).

Although document examiners avoid any mention of graphology, graphologists have made a considerable contribution to forensic examination. Furthermore, a greater awareness of graphology could help forensic handwriting examiners gain a deeper understanding of the signatures they are examining.

Contribution to Forensic Handwriting Examination

- Movement/spacing/form- the key elements in handwriting: This grouping was first suggested by Robert Heiss, a German graphologist who was also a leading figure in psychology, philosophy and criminology.

- Speed- The main work on this aspect was carried out by Robert Saudek, a graphologist, who defined letter, syllable, word and sentence impulse.

- Rhythm- Ludwig Klages, a graphologist, was the instigator of research in this area, followed by Roda Weiser, also a graphologist.

- Line quality- With his work on amorphous, homogeneous and granulated strokes, Rudolph Pophal, a graphologist, was the catalyst for important work to be carried out in this important area. Walter Hegar, a graphologist, showed how stroke (the ductus) is directly linked to a writer's instincts, so making it difficult for others to fake.

- Spacing- The symbolism of space was outlined by Jules Crepieux- Jamin and Max Pulver, both graphologists.

- Form- It was Saudek again who outlined for examiners those factors influencing letter formation. They are: mechanical aspects; writer's graphic maturity; writer's relative speed of writing; the copy-book learned; the writer's nationality; the writer's visual sensitivity; the writer's power of graphic expression; the writer's knowledge of foreign languages; the writer's physical condition; and whether the letter under examination is at the beginning, middle or end of a word.

- Ill health- Graphologists such as Florence Witkowski and Patricia Wellingham-Jones, have demonstrated how manic depression, drugs, alcohol, schizophrenia and paranoia affect writing.

- Unconscious movements- Renna Nezos, a graphologist, has shown how certain unconscious movements (e.g. stroke tension, alignment, hooks, level of continuity, primary/secondary width and word spacing)- when seen in combination- can suggest two sets of writings or signatures are by the same author.

Aspects where Graphology can help Forensic Examiners

Disguised Signatures

Used by people to avoid responsibility

Moving beyond 'like for like'

Forensic examiners take into account environmental factors (writing instrument, writing position, etc.) and health (drug taking, mental health, eyesight problems, ageing, neurological diseases - that have an impact on motor control).

But there is a reluctance, because of the reasons stated above about 'science', to consider the effect of personality on handwriting, the area of interest to graphologists.

An example is the area of disguise. If examiners understand graphology and see dishonesty in known writings, they- instead of initially concluding different writing means possible forgery- can get a head start by testing for disguise.

It is a rule that only 'like for like' comparisons can be made in forensic handwriting reports. For example, if there is a small hook at the start of a stem, the only acceptable comparison for court purposes is with another hook at the start of a stem and not, for example, at the start of an. Capital letters cannot be compared with cursive writing. Initials cannot be compared with complete signatures.

Although these 'inexact' comparisons cannot be included in a forensic report, a graphological understanding of the psychology behind 'inconspicuous movements' (indicative strokes or typical gestures) can give document examiners a faster route into deciding whether or not a piece of writing is authentic.

Indicative strokes can be copied, but to do so, while simulating a range of other characteristics, such as fluency, up slant angles, pen lifts, baselines, crest lines, letter spacing- in combination- is difficult.

Case Examples:

- The known signature contained narrow pinched angles on the base line of oval structures (which graphologically means a person is easily offended and sometimes vindictive in personal matters). In the same case the questioned signature contained arrow head, dots, tics and slashed forward placed bars. All these characteristics suggested considerable irritability so though the signatures look very different, they were not automatically dismissed as being by different authors.

- In the known signatures, the lower zone loops came back up and stopped at the down stroke without cutting through. Graphologically this meant that the writer was prone to hesitation and an unwillingness to follow through. In the questioned signature, a similar tendency towards hesitation was seen in the 'suspendu' strokes (strokes that do not reach down to the base line) and bars placed to the left of stems.

- In the known signatures the final stroke was pulled strongly below the base line, graphologically a sign that the writer needs the last word in an argument. In the questioned signature there were triangular pyramid stem structures, a sign of stubbornness. So again, signs of a similar personality were present in both the author of known and the author of the questioned signatures, a situation that triggered further examination.

Conclusion

A person's writing may change but what the graphologist can see is the fundamental consistency of the character over time. With graphological insights a forensic examiner is able to check areas they might otherwise miss.